Cape Town Jazz Fest captivates with smorgasbord of sounds

As a coming-of-age event, the 21st Cape Town International Jazz Festival (CTIJF) hit all the right notes. With more than eight hours of music across four venues on each of two consecutive nights, one needed handfuls of vitality and energy supplements to catch 10 of the 29 performing artists brought to the Mother City to celebrate the return, after five years of waiting, of the CTIJF.

Kokoroko member Sheila Maurice-Grey at CTIJF. Photo: Fuad Esack

Kokoroko member Sheila Maurice-Grey at CTIJF. Photo: Fuad Esack Bokani Dyer. Photo: Fuad Esack

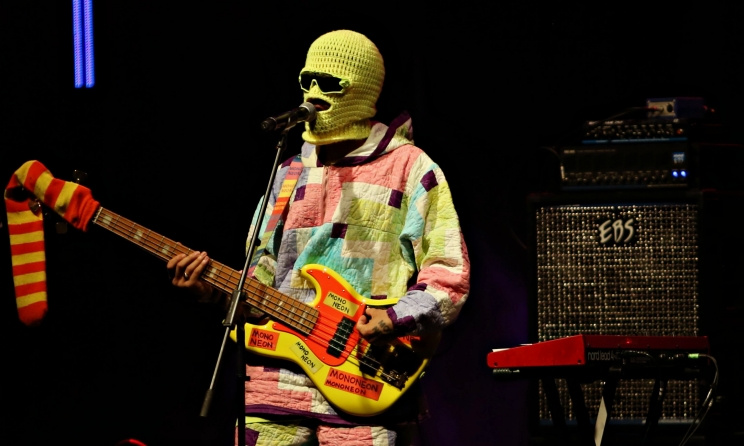

Bokani Dyer. Photo: Fuad Esack MonoNeon. Photo: Fuad Esack

MonoNeon. Photo: Fuad Esack Nduduzo Makhathini. Photo: Fuad Esack

Nduduzo Makhathini. Photo: Fuad Esack Hilton Schilder. Photo: Fuad Esack

Hilton Schilder. Photo: Fuad Esack Benjamin Jephta and Keenan Ahrends. Photo: Gregory Franz

Benjamin Jephta and Keenan Ahrends. Photo: Gregory Franz

From mourning the death of a South African jazz great, through the political swamp of race classification, to the esoteric and spiritual; from the youthful energy of the next generation of performers to the quiet serenity of the mature masters, variety and diversity were on display in abundance.

Friday

Darshan Doshi Trio (India/US/UK)

Darshan Doshi is regarded as the busiest drummer in India, not for his energetic stick work behind his extensive drum kit, but for the volume of films and other gigs for which he is the first-choice drummer. The sidemen in his trio for the CTIJF were Mark Hartsuch, an American saxophonist and producer, and Tony Grey, a British bass player, composer and producer.

When we met for a short interview with the band on Friday, before their set early that night, the creative energy and anticipation were evident. This is a new trio and there is no info about the band on the internet. Doshi says: “We played together during COVID, trying a few things online … then Mark and I recorded five songs together after COVID, and released an EP called Better Than Sax.

Mark Hartsuch chips in: “After bumping into each other at a concert somewhere, there was a text saying, ‘We should play together sometime’, and before I knew it, we were in a studio and recording.”

How did Doshi, a drummer raised in a different culture, in an environment of Eastern and mid-Eastern music, come to be leading a jazz trio?

“My teacher and mentor is Ranjit Barot. When he started playing with John McLaughlin in 4th Dimension 10, 12 years ago, I started listening to McLaughlin’s albums. It was like a creative earthquake.”

A question to the trio as a whole: What do you look for in a musician when you’re putting a combo together, what qualities, what elements?

Hartsuch, who is as much the spokesperson for the trio as Doshi, says: “It’s all about timbre. Michael Brecker sounds different to John Coltrane, even playing the same piece. You’ve heard of guitar envy, wanting to play like Santana or Di Meola? I have envy for the way Brecker hits his notes.”

Tony Grey – the older, quieter one of the trio, and a nephew of John McLaughlin – says: “Darshan is definitely not Steve Gadd, he’s recognisably different, his playing has a different timbre.”

Given that this was the inaugural live gig for this band, and that they had a little more than four hours before their call, we wrapped up the interview with some chatter about how they play with structured improvisation.

Their set was great, kicking off Friday night’s music with a high-energy, solid jazz-fusion element. The structured improvisation of the trio, driven by Doshi behind his huge drum kit, was unmistakable. A group of eight youngsters filed in after the third number, sliding into empty seats in the front row, bobbing and bowing in unison to the music, looking a lot like a mixed flock of pigeons and doves pecking seeds from the lawn, talking animatedly between numbers, and clearly loving every moment. The Darshan Doshi Trio, individually, or in any combo, are well worth checking out.

Hilton Schilder (SA)

The Schilder name is synonymous with Cape Town jazz, and the mantle of now being one of the elders rests comfortably on Hilton’s shoulders. Composer, pianist and multi-instrumentalist, his mastery of 16 instruments, both indigenous and conventional, is astounding. Hilton, along with the likes of Basil Coetzee, Robbie Jansen and Mac McKenzie played a central role in creating the unique sounds of Cape Town jazz.

However, he does not want to be called a jazz musician: “When I say I am a jazzman, I’m closing myself off to all the other avenues that I compose in because I compose using classical influences, folk music, Middle Eastern music. Calling me a jazz musician would limit me to a particular style.”

From the beginning, his set felt more like a lament: bluesy, rooted in sorrow, with the plaintive wail of the violin counterpointed by a demanding urgency in the drumming. Then came the sad announcement. Schilder’s close friend and collaborator in goema, bandmate in The Genuines, Gerald ‘Mac’ McKenzie, was cremated that day, having passed away a few days ago. The entire performance was dedicated to him. Schilder, a true professional, chose to go ahead with the gig, which was as much an act of mentoring the young members of his quintet (they’re all in their 20s). Their youthful energy and promise was the perfect antidote for the sadness. Well done Clayton Pretorius (bass), Shahima LaKay (violin), Kurt Bowers (drums) and Ruby Truter (vocals) for the pleasure you gave us in a moment of grief.

Kokoroko (UK)

Named as a band to watch by The Guardian in 2019, Kokoroko is a London-based group who play a fusion of jazz and Afrobeat. Scheduling issues (four stages, with slightly staggered starting times) made it tricky to get more than a taste of a band. We had planned to pop in to catch a bit of Kujenga before Kokoroko, but the lingering sorrow of the Hilton Schilder set demanded some soulful solitude before catching the next act. So 15 minutes of Kokoroko was all we got musically, but we did get to meet a few of the band members at a press conference earlier. They are confident answering questions, and about their vision. They also have an answer to what it takes to make collaboration among a diverse group work: flexibility, no egos, and room for everyone’s voice. They’re a young, enthusiastic and impressive eight-piece band, and their music bristles with funky vibes. It’s a pity we couldn’t stay longer, but an icy wind around the outside stage where they were playing drove us indoors to where The Prisoners of Strange were about to start...

Carlo Mombelli & The Prisoners of Strange (SA)

We had a 30-minute interview scheduled with the band early on Friday afternoon, only to find that we had to share the slot with another media team. But the delightfully energetic synergy between Carlo Mombelli and Siya Makuzeni was infectious, more than making up for the late start.

Twenty-one years ago, at a concert at Emmarentia Dam in Johannesburg, was the first and last time I saw The Prisoners of Strange. My memory of the band was only Carlo Mombelli and Marcus Wyatt. Sure, there were other musicians on stage, but these two stood out. I mention the concert, asking if the line-up has changed much since then. Carlo and Siya look at each other, and she says, “The Bassline concert?” Carlo is almost bouncing in his seat, nodding vigorously. “Yes, yes, it was. But the line-up is the same now as it was then. We come together as a band whenever we can, but in between we have other gigs.”

Was there ever a mentor-mentee relationship between you and Marcus Wyatt, or other band members? “Yes, of course,” Mombelli says. “With all of us. It’s a two-way street mentoring.”

An article on All About Jazz has this to say: “Carlo Mombelli remains one of the most restlessly creative forces in South African jazz.” I ask him for comment on it, on where the restlessness comes from. “I’m inquisitive,” he says, “There’s too much that needs to be seen, heard. I have so many names. My mother has a name for me, so does my wife. My children call me something else. So many names, so many labels, but I’m still the same person.”

Their set was everything I expected and nothing like I imagined, which is as it should be with this band. Imagine yourself locked in an auditorium with an Einsteinesque creative musical genius and his collaborators. You have no control over the sounds, the images that the feelings evoke – as this is a dream world not of your making. It’s a world of crooning and bells, partial chants, singing bowls, and insistent trumpet lines; a drummer and bassist who support and enhance each other, yet are separate and distant. This is just one of the places their music took me.

They played a couple of songs from their 2010 album, one being the title track ‘Theory’, the other ‘Religion’. Mombelli talks about his father’s dream of his son becoming a chef like him, as an intro to ‘Little Window in the Kitchen’ off his Stories album. Next, a song from a walk around the Mombelli garden: ‘Basil, Roses, Lemons, Love’. If these song titles seem too ordinary to be avant-garde jazz, just sit in the room where they are being played.

Led by the inimitable composer and bassist Carlo Mombelli, The Prisoners of Strange are: Siya Makuzeni (vocals, trombone), Marcus Wyatt (trumpet), and Justin Badenhorst (drums). You only need to see Carlo Mombelli and The Prisoners of Strange perform once to be left with unforgettable impressions, and a strong desire to see them again.

Saturday

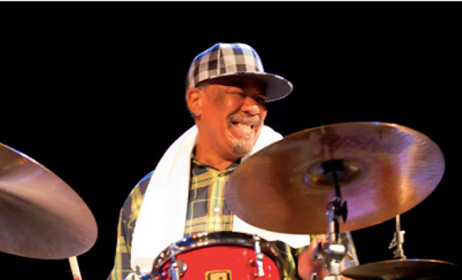

Mervyn Africa (SA)

Charming, confident, self-assured, with a warm and slightly mischievous smile, Mervyn Africa got the Saturday night gigs off to an excellent start. It was great to see one of Cape Town’s jazz elders, who has been absent for decades, back in action. At the age of 73, “I’m just getting started,” he says.

Mervyn Africa, along with Bernie Lawrence (another veteran) on bass, bridged the generational divide by playing alongside Keegan Steenkamp on trumpet and Carlo Fabe on drums. Their first number, ‘In Our Hands’, set the tone for the night, and was followed by a song by Dudu Pukwana, another of South Africa’s legendary musicians who died too early.

Turning from the grand piano he had been playing to the electric piano at the edge of the stage, he paused, looking like he wanted to be somewhere else. “I don’t like this piano,” he said. But he played it and played it well. Electric or grand, his piano playing is a delight, and we didn’t want to leave to catch the opening of Benjamin Jephta’s set. Sigh. For every privilege, there’s a penalty, or so it seems when faced with choices of this nature.

Benjamin Jephta (SA)

Benjamin Jephta’s set explored the themes on his new album, Born Coloured, not Born-Free. In a South African context, the born-frees are those children (black, Indian, Malay, mixed race, etc.) who were born after 27 April 1994, the date of the first fully democratic elections in the country. Although Jephta was born in 1992, it’s close enough to 1994 for him to be considered born-free. In terms of racial classification, ‘coloured’ is a cumbersome, almost undefinable category. Pre WW2, coloured was a social category rather than a legal designation. With the introduction of the Population Registration Act of 1950, people of mixed blood were defined as coloured, which was given the meaning of “not white, not native”, a classification that was often applied in an arbitrary way.

Jephta’s compositions draw on traditional South African styles such as goema/Cape jazz and marabi, as well as modern African music idioms such as gqom, kwaito and hip hop. During his performance, the bassist and composer reflected on his experience as a coloured in post-apartheid South Africa. In a series of interludes between compositions, he dissected and interrogated this experience. In one, he talks of the resilience of the coloured people, particularly his grandmother, Gadija Jephta, for whom ‘Gadija (Pt. 1)’ and ‘Gadija (Pt. 2)’ were written.

Jephta spoke of reclaiming his African identity while remaining culturally coloured, before playing ‘The Ben-Dhlamini Stomp’.

Gretchen Parlato & Lionel Loueke (US/Benin)

Beninese guitarist Lionel Loueke has played and toured with his mentor Herbie Hancock for the past 19 years. He and Gretchen Parlato first met in 2001 when they were both auditioning to be accepted for the master’s programme at the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, and happened to hear each other’s audition. The panel of judges included Herbie Hancock, Terence Blanchard and Wayne Shorter.

His collaboration with Gretchen Parlato began shortly after the audition and they first recorded together on her eponymous 2005 album. They are, in many respects, an extraordinary duo. Loueke’s guitars are out-of-this-world art pieces, and his mastery of the instrument is superb. Both of them scat freely, Loueke coaxing melancholy or joyous or surprised notes from his guitar, with Parlato’s rhythmic phrasing adding sonic layers to create sound tapestries. Their live performance, while musically excellent, is visually stilted, except for the potentially striking and stylish composition the two of them present. They are both extraordinarily talented, but their music is cerebral, and the almost constant comings and goings of the audience during compositions did nothing to enhance the experience.

MonoNeon (US)

Again, a performance that was limited by scheduling issues (this overlapped with Gretchen Parlato & Lionel Loueke and Moonchild). Although he is right-handed, MonoNeon plays left-handed on an upside-down right-handed bass guitar. “This is the way it was put into my hands,” he says. In another interview, he says he was four when his dad gave him a guitar, and his mother says, “He just flipped it over!” Whichever story is true, this is an exceptionally talented musician. His music is a blend of styles and genres, such as funk, jazz and hip hop, fused with exquisite musicianship. He has been working on a new slapping technique, and says the upside down guitar makes slapping more difficult. But it does allow for heavier than normal string bending on the upper strings.

It’s easy, almost compulsive, to dance to his music, and he and his backing band had a significant number of normally sedentary festinos dancing in the aisles. His crocheted blanketed look is an expression of love. He says his grandmother made him one, and it was such a labour of love that he wears it out of love for her. Which is cool, and touching, but it doesn’t explain the sock over the head of his bass.

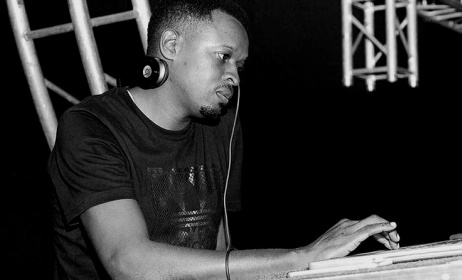

Bokani Dyer’s Radio Sechaba (SA)

Radio Sechaba was inspired by Bokani Dyer’s exploration of nationhood and identity in South Africa – in a way reflecting Benjamin Jephta’s dissection and interrogation of racial identity. So no surprise that Jephta is the bass guitarist for this gig. Sechaba means ‘nation’ in Setswana and, in his words, “I had long been thinking about what makes a nation, in relation to the current South Africa, and how to capture that in my music.”

Born in Botswana and raised in South Africa, Dyer’s upbringing influenced his perspective on these issues. While doing his master of music degree, he dug into whether young South African jazz musicians address social issues through composition, which led to his concept of Radio Sechaba. Fronting a six-piece band, Dyer put on an outstanding performance. In a small departure from his usually instrumental compositions, he sings a lot more in Radio Sechaba. A haunting performance, soulful, occasionally angry, and challenging preconceptions in ways that need more than one hearing.

Nduduzo Makhathini Trio featuring Omagugu (SA)

This trio/quartet was the revelation of the festival. Nduduzo Makhathini is rooted in the symbiotic relationship between music and ritual practices in Zulu culture. As an academic, his research focus is on music and spirituality, something that comes through clearly in his performances. Tom Fletcher, writing for blackhistorymonth.org.uk, says: “Makhathini has earned widespread acclaim for the genuinely spiritual transcendence of his music. For Makhathini, a healer and educator … music has never merely been about aesthetics or idioms.” His music goes deep – beyond the ears, reaching past the mere physical parts of our being. There is a distinctly uplifting spirituality to the way his music and words move the audience, perhaps something to do with the way he integrates the spiritual and educational within the music.

Moving away from his piano, Makhathini regularly spoke to the audience. In one of the short talks he gave between numbers, he spoke about imagining the unimaginable, about “life and death and the unknown all collapsed into one sound, seeking a way to surrender to something more potent … where the band transposes in a way they become a study in playing music of the self to re-language the un-languageable.”

Ron Deutsch, in an article titled In Conversation With the Ancestors, writes, “ … he is also conducting a spiritual ceremony, using the piano and his voice to call upon his Zulu ancestors … to offer some spiritual relief and raise our consciousness.”

Omagugu, Makhathini’s wife, occasionally came onstage to sing. And she sings beautifully, unquestionably helping raise our consciousness. With sensitive and solid support from Zwelakhe-Duma Bell le Pere (bass) and Francisco Mela (drums), this is a performance that will live a long time within every person who was there. The audience was transfixed, transported, and the standing ovation at the end of the performance was as spontaneous as it was sustained. He touched us all, for the whole of his show. There was just no more room for any other music after that.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments