Digital technology and the music recording industry in Kenya

Research title: 'Digital Technology and the Music Recording Industry in Nairobi, Kenya'

Publication: Music, Digitization and Mediation (MusDig)

Author: Andrew J. Eisenberg

Year: 2015

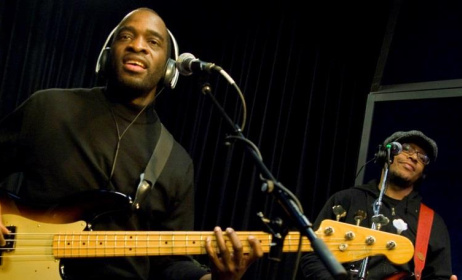

Influential Kenyan producer Tedd Josiah. Photo: www.standardmedia.co.ke

Influential Kenyan producer Tedd Josiah. Photo: www.standardmedia.co.ke

'Music, Digitization and Mediation (MusDig)' was a five-year research programme engaged in mapping and analyzing the far-reaching changes to music and musical practices by digitization and digital media. Directed by Professor Georgina Born at the University of Oxford from 2010 to 2015, MusDig set out to investigate the ways in which developments in the realm of digital technology have affected and continue to affect music and musical practices across the world.

This article is an extract from research by Andrew J. Eisenberg on the digitisation of the recording industry in Kenya. “My core aim, developed in dialogue with Professor Born and other MusDig researchers, was to examine how the advent and rapid development of digital technologies of musical production and distribution have impacted the sounds and economics of commercially recorded popular music in Kenya,” the researcher writes in his introductory remarks.

Nairobi as a music production hub

In the decades following World War II, Nairobi emerged as a regional hub for commercial popular music production. By the late-1970s, the city boasted a large community of talented musicians from across the region, a world-class recording studio owned by CBS Records (now Sony Music Entertainment), and a profitable record pressing plant owned by PolyGram (now part of the Universal Music Group).

While this dynamic African recording industry produced a great variety of music during the 1960s and 1970s, sales dropped precipitously in the 1980s, leading to a virtual collapse of an industry that must have seemed unstoppable just a decade earlier. By the end of the 1980s, CBS and the other multinational record companies that had begun to set up shop in Nairobi had pulled up stakes and left, studios were no longer being built or upgraded and PolyGram’s record pressing plant was in mothballs.

The advent of the audio cassette, which enabled large-scale piracy and informal sharing (‘cassetting’) while "flooding the market with cheap copies of Western, soul, disco, rock and reggae records", is often named as the sole cause of the downfall of Nairobi’s recording industry. But other economic and political factors also came into play. One seed of the collapse was planted in the 1970s, when ‘Africanization’ policies forced a transfer of ownership in the thriving music production and distribution companies in Nairobi’s downtown River Road

The once internationally marketable Nairobi sound began to go stale, suffering from an acute lack of originality whereby "one melody was taken and flogged to death". Meanwhile, Nairobi’s recording industry was also hit by a general economic slowdown and stifling import, visa and foreign exchange restrictions. Commercial music recording in Nairobi remained in a severe slump for much of the 1980s and early 1990s. The sole bright spot was the continued viability of independent producers.

There was nothing surprising about River Road’s resilience. The neighbourhood had already become known for services and products related to music production and distribution (such as printing, electronics, instrument sales, etc.). As the beating heart of Nairobi’s informal economy, however, it was also the centre of the media piracy industry.

Whether or not they themselves were involved in pirating music, River Road producers had an intimate knowledge of ‘the pirates’ and how they worked, enabling them to clamp down on the unlicensed distribution of their own material or find ways to adequately compete with it. They became famous for getting their music to market with great efficiency, using strategies like selling phonograms off the back of a lorry fitted with loudspeakers. Even now, in the second decade of the 21st century, they manage to sell tens of thousands of copies of their new releases by keeping prices low and bringing products directly to consumers.

The opening up of Kenya's airwaves

Kenya’s first privately owned FM radio station, Capital FM, went live in 1996, ending half a century of government control of the airwaves. As a result, in the words of pioneering Kenyan urban producer Tedd Josiah, "When the FM stations came, the music they were playing was just hip-hop, R&B, rock - everything apart from Kenyan music". Entrepreneurial Kenyan musicians like Josiah saw an opportunity in this radical transformation of the Kenyan media landscape and responded.

Though catalyzed by the new media landscape, the urban youth music genres of Kenya’s millennial music boom must be understood as products of a longer history of urban Kenyans’ engagements with foreign (specifically American and Jamaican) popular music.

While small digital recording studios played an important role in the early days of the new music boom, the first local, self-consciously ‘urban’ productions to achieve significant airplay on Kenyan FM radio came out of studios stocked with tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of digital and analogue equipment, mastered and pressed on CD to international standards in Europe. In 1996, the year that the first private radio stations came on the air, Bruce Odhiambo, an experienced musician and recording engineer who had taken up a job in the advertising industry, produced an album for the R&B vocal group Five Alive using his company’s Apple Mac-based recording studio. The album received considerable airplay on FM radio, and was heavily promoted on Kenya’s first private television station, KTN, by music show host Jimmy Gathu.

A new sound for a new industry

Around the same time, Tedd Josiah, who had made a name for himself as a member of the Christian R&B vocal group Hart, was working with young Kenyan hip hop and dancehall artists at Sync Sounds Studio, a MIDI-equipped facility set up by members of Mombasa Roots, a successful Kenyan band formerly on Polygram. His aim, as he often stated, was to nurture the distinctly Kenyan urban youth sound that he saw as emerging organically from the artists he and his collaborators discovered. These artists included dancehall singer Hardstone, who could mix Kikuyu and Jamaican patois, and the rap group Kalamashaka, who came with a raw, Sheng’-inflected style of Swahili rap developed on the streets of Dandora slum. After a couple of years, Josiah moved to another studio, Audio Vault, set up by Mike Rabar of the DJ outfit Homeboyz and David Muriithi, an accountant with experience DJing and managing bands in Manchester, England.

Audio Vault’s activities as a record label demonstrated both the challenges and the potential for success facing the emerging new recording industry. The company made money through sales (mainly audio cassettes) - but only by working directly with the ‘pirates’ on River Road due to the lack of a working legitimate system of distribution. This was a tenuous system of distribution and arguably unsustainable for the larger industry. But Audio Vault also realized other ways of generating revenue from recorded music - ways particularly suited to its location in a regional economic hub that hosts foreign embassies, United Nations departments and a large NGO sector. Positioning their artists as purveyors of urban youth culture, Josiah, Muriithi and Rabar secured event and endorsement deals with deep-pocketed organizations like the UN and British American Tobacco. At the same time, they leveraged Josiah’s reputation to bring in commercial audio work (such as radio advertisements and television scores).

By the time Audio Vault began operations, it was clear that a new recording industry had emerged in Nairobi. Almost two decades later, observers in Nairobi described this industry as a set of multifarious and shifting networks, strategies and practices that might someday stabilize into something more "structured", but which is yet to do so. For instance, one successful producer opined that Nairobi’s new recording industry "is not quite an industry as it lacks managers, publicists or promoters. There’s all these things that are still missing, and it all comes to not having enough money to employ these people to do it". But others also frequently emphasized the dynamism that stems from the industry’s underdetermined, improvised character. As always in urban Kenya, where the notion of jua kali (informal economic activity) permeates everything from official government policy to everyday discourses of survival, lack is a problem (even a pathology) but does not equal blight. Rather, it inaugurates a context in which rapid change (indeed development) can take place, precisely because very little is prefigured and everything is negotiable.

One factor that does grant Nairobi’s new recording industry a sense of coherence is the persistence of the old recording industry as a relatively distinct geographical and institutional entity. Artists and producers in Nairobi’s new recording industry look to River Road as both a positive and negative example in constituting their own aesthetic and entrepreneurial approaches.

The shift from compact discs to online sales

The establishment of the CD as a common medium for music in Kenya in the early 2000s initially offered local music entrepreneurs some hope that legal distribution might be revived. The shiny new medium appealed to consumers of Kenya’s new youth-oriented music genres (hip-hop, R&B and rock) and its wholesale cost was low. But hope quickly evaporated as the CD proved an even better medium for piracy than the analogue cassette. Even the pioneering Kenyan crew Ogopa DJs, whose catalogue played constantly on Kenyan radio around the turn of the 21st century, failed to bring in significant revenue from CD album sales, with a 'successful’ Ogopa album typically only selling around 3000 units.

The popularity of 'Kenyan madness' drove some local entrepreneurs to become interested in testing out whether Kenyans abroad might actually pay for access to Kenyan music online. In 2003, talent manager Fakii Liwali teamed up with a young computer programmer named Bernard Kioko, who would later make his own mark as founder and CEO of the digital content provider Bernsoft, to create an Internet platform for Kenyan music called MyMusic. The project was short-lived due to a shake-up within the company to which they had sold a large number of shares. But Liwali maintains that it was successful enough to prove that Kenyans at home and abroad were willing to pay for Kenyan music online.

By 2012, Kenya’s largest mobile network operator, Safaricom was running three separate music portals, each geared toward a different type of service. The most profitable was Skiza, a subscription service offering caller ring back music at five Kenyan Shillings per song per week. With around 4 million subscribers, it was grossing at least $10 million per year (probably more), the vast majority of which (85% before VAT) was going to Safaricom.

The move to talent management

Significantly, Safaricom and a number of digital content providers were moving into talent management, an area that had not seen a great deal of growth or entrepreneurial activity since the millennium youth music boom. MTech East Africa is an example of this. A subsidiary of MTech Nigeria that was then headed by Ikechukwu Anoke, the company was turned into a talent management agency specializing in connecting Kenyan music artists with Nigerian collaborators (primarily video producers and artists). This move was attributed to the increasingly competitive business environment. In light of the entrance of Indian firms like Spice into the digital content market, content providers needed to have something special to offer to artists. For MTech, this was a connection to the Nigerian industry and market, and a CEO who could personally attend to an artist’s needs.

Intellectual property law

Just as m-commerce (commercial transactions conducted electronically by mobile phone) was exploding onto the Kenyan scene, Nairobi’s recording industry was beginning to feel the impact of yet another transformative global process: the international harmonization of intellectual property (IP) law. Proponents of intellectual property law reform in Kenya maintain that it will ultimately serve to eliminate the lingering structural problems of the music recording industry. Whether or not this turns out to be the case, such “formalization” will take years. In the meantime, as new IP laws, regulations, procedures and institutions are introduced, ideas about musical authorship and ownership shift and change along with, and in relation to, the industry’s dynamic systems of production and distribution.

Re-published with permission from Andrew J. Eisenberg. Download the full report below or here. To read more MusDig research on other music industries, visit the MusDig website. The research was funded by the European Research Council's Advanced Grants scheme, research project number 249598 titled 'Music, Digitization, Mediation: Towards Interdisciplinary Music Studies (2010-15), directed by Prof. G. Born and based at the University of Oxford.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments