What's wrong with the Official Afrobeats Chart?

For popstars in Africa, the introduction of the Official Afrobeats Chart in the UK, now in its fourth week, represents victory in a struggle for global recognition. The songs and artists ranked under the rubric are hardly strangers to the Official Charts Company, which curates the new chart. Afrobeats songs occupied the UK Singles Chart Top 40 for 86 weeks in 2019, and artists from Africa habitually fill premium venues in the UK. A chart they can call their own is particularly satisfying. It also amounts to a coveted goal to aspire to.

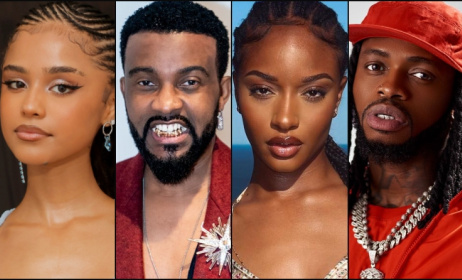

NSG.

NSG.

Despite the notion that the Official Afrobeats Chart is a logical next step in the genre’s ongoing global journey, it has also invited much criticism. Which is hardly a surprise. It would be unexpected if a move this ground-breaking was attended by zero opposition, and one would ignore the sceptics if they didn’t make such convincing arguments.

What then is the trouble with the chart? The first issue that cynics cite is the Afrobeats label itself. Though over-flogged, it still retains some validity: if we recognise a multiplicity of music from West Africa and the rest of the continent, then tagging all popular music under Afrobeats is unfair to the variety of African sounds, the argument goes. Afrobeats has been marketed as a genre. Genres, at their core, are identified by similar musical elements that create a signature sound. Reggae, hip hop, Afrobeat, and EDM all rely on particular rhythmic patterns and production techniques that group them together. Why does this not work for Afrobeats?

Its champions chafe strongly against the suggestion that it suffers from an identity crisis, yet on the Official Afrobeats Chart one hears Wizkid’s 'Smile' as reggae, Simi’s ‘Duduke' as highlife, and Aya Nakamura’s ‘Jolie Nana' as reggaeton – while NSG, which topped the chart in its first week, offers a sound totally different from all of the above. How does such a diverse array of sonic persuasions fall under a single chart that is supposedly steered by a genre?

This harks back to the World Music discussion. To remind readers, World Music is a western music category that basically groups anything considered as ethnic, indigenous or folky. Beninese legend Angelique Kidjo currently holds the Grammy statuette in that category. Ghanaian producer Juls, a strong Afrobeats architect who recently made the Recording Academy's class of 2020, intends to protest the compression of nearly every sound outside popular music into a single category; he wants to see more African categories at the Grammys. Perhaps a similar campaign is needed for Afrobeats – in order to resolve the confusion. Or does this go against basic marketing principles in a globalised world?

For many industry watchers, it’s no surprise that the Official Afrobeats Chart is based in the UK and ranks its artists on the listening habits in the country. According to many accounts, even the term ‘Afrobeats' was coined at radio studios in the UK. One may say, therefore, that Afrobeats was curated by and for the African community abroad. The UK, which is famous for its vibrant African and Caribbean diaspora, is also a massive consumer of the genre, and therefore a key demographic in the Afrobeats universe.

In 2017, Nigeria’s Mr Eazi, a valuable Afrobeats influencer, disclosed to me that the UK represents a key constituency of his fan base. That Burna Boy, Davido and Wizkid have all held sold-out shows in the UK is added proof. If the UK created and nurtured the Afrobeats industry, it should reap the benefits without too much backlash. Besides, an official Afrobeats chart provides mileage for African music, regardless of where the chart is based. It adds to the momentum that African pop is enjoying globally and represents yet another feather in Afrobeats' cap.

If the impression is floated, however, that the chart also speaks for the biggest songs in Africa, then it should raise eyebrows. UK's NSG debuts at No 1 ahead of those based in Africa? What metrics could the group possibly have to beat Africa’s biggest? Let's compare NSG's YouTube numbers at the time of writing to those of Burna Boy. NSG released 'Lupita' about the same time Burna Boy published 'Wonderful'. As of 9 August NSG's video had amassed 1.1 million views while Burna Boy's stood at 4 million. Rema's 'Woman', also released in early July, secured 1.3 million. Here is the crux: the chart is based on the listening habits of inhabitants of the UK and so it makes sense for NSG to have led the Africans.

Is one to deduce from the above that the diaspora favours diasporan acts over their African colleagues? This seems to be the case, and understandably so. But there's is another level to the question of the chart's credibility – one of geographical and cultural context. Burna Boy's view on the matter, submitted during an NME interview recently, is particularly instructive. Despite lauding the intention of the chart, he challenges the legitimacy of its curators: “My only thing is, whoever is doing the Afrobeats chart in the UK should not even be in the UK. If you’re doing a grime chart, then you can be in the UK, but it’s not fair for the people who have really based their lives on this, who have really grown up on this. This is their culture. It’s a lot bigger than what the charts are presenting it as."

In all this, it is important to note that the chart is backed by the BBC, a massive media monolith that brings financial muscle and global focus to the initiative. There appears to be a centralised agenda to publicise the genre – ultimately due to its potential to be extremely profitable. Similarly, the Official Charts Company comes to the table with a 60-year track record that is largely unblemished. Together, the two organisations command a level of authority and perceived credibility that their African counterparts can only dream of. This calls up the issue of higher media standards, revenue transparency and a united music industry in Africa. The rise of third-party bodies funded by the African music industry itself to establish trustworthy tastemakers is vital if the continent wants to command its fate. Unless the lion offers its account, the tale of the hunt will always cast the hunter as the hero.

What we are seeing with the Afrobeats genre and Official Afrobeats Chart is the creation of a cohesive, defragmented product packaged for global consumption. Marketing 101. It is wrapped in a box with a bow, and on it is a card that says, "From Africa, with love". Whereas in Africa we want every culture, language and experience to be reflected in a title or an idea, the PR gurus in the UK and the US know that simplifying a complex entity is the smartest route towards profitability. Why complicate things for a global cohort of young listeners with short attention spans when you can present them with a perfectly packaged genre called 'Afrobeats' – "from the country that is Africa"?

Perhaps, as is the case with other genres, nuance in the form of Afrobeats subgenres will emerge with time (just think of the hundreds of subgenres in jazz or rock that were coined throughout the years), but this will only be possible when tastemakers on the continent are able to make valuable cases in the Afrobeats argument. There may yet be a chance for many African media houses and the industry itself to assume their rightful positions as cultural gatekeepers: if we can purge ourselves of the mind-numbing sensationalism, lack of industry cohesion and contradictory messaging, Africa should be able to forge its own collective identity before it's assimilated by the rest of the world.

The Official Afrobeats Chart is updated every Sunday via the Official UK Afrobeats Chart playlist on Spotify. The full chart appears on the company’s website.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments